European Origins

|

| Coffee first became widely available in Europe around the middle of

the seventeenth century, as a result of the expansion of the international shipping trade.

The earliest coffee brewing methods involved boiling the coffee together with water, with

the optional step of

filtering out the grounds. This resulted in a overly bitter and unpalatable beverage,

which generally fell out of favor until the advent of the Infusion brewing

process in France about 1710. This process involved submersing the ground coffee, usually

enclosed in a linen bag, in hot water and letting it steep or "infuse" until the

desired strength brew was achieved. In this era, the "coffee pot" was a metal

vessel used primarily as a means of dispensing the brewed coffee, either via a spout or by

one or more spigots jutting from the body of the vessel. |

Throughout the eighteenth century, coffee culture and

technology continued to evolve. More complex methods of separating the grounds from the

brew were developed - some involving ingenious screw mechanisms and collapsible bags. This

era also saw the evolution of ever more elaborate urns for dispensing the coffee,

including some that dispensed coffee from an inner chamber and hot water from an outer

jacket, which also served to keep the coffee warm. Indeed many innovations of the era were

designed to keep the coffee hot either by employing an insulating jacket of water or air

surrounding the pot, or a spirit lamp located in the base (or both).

It was about this

time in Europe that the notion that coffee should never be boiled was gaining

acceptance. One of the primary advocates of this idea was Jean Baptiste de Belloy,

Archbishop of Paris, who favored the French Drip Pot. In this method of brewing

coffee, two chambers are stacked one upon the other, with a cloth filter placed in

between. Finely ground coffee is packed into the upper chamber and boiling water is poured

over it. As the coffee brews, it slowly drips into the lower chamber, from which it is

served. Again, the slowness of the brewing process often leads to a tepid cup, but the

innovative minds of the era were soon at work on the problem. The American scientist and

adventurer Benjamin Thompson (Count Rumford), invented a drip pot with an insulating water

jacket, and added his voice to those promoting coffee without boiling in his essay, "Excellent

Qualities of Coffee and the Art of Making it in the Highest Perfection." |

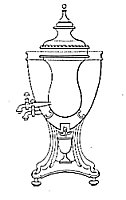

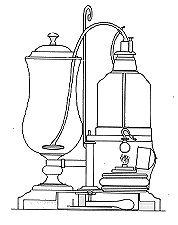

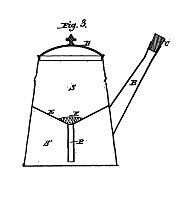

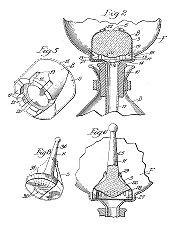

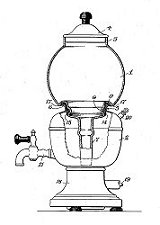

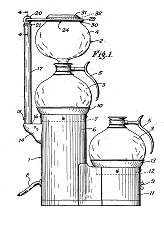

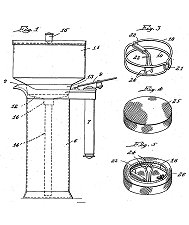

Palmer's 1786 patented

coffee urn with spirit lamp,

hot water jacket, and

dual spigots.

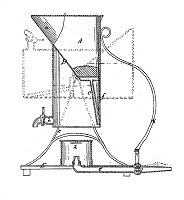

Count Rumford's insulated

French Drip Pot.

|

|

| By the beginning of the nineteenth century, all the elements were in

place for the development of the glass

vacuum pot. Amateur scientists were busy experimenting with vacuums, vapor pressure, and

fluid dynamics; efficient coal-fired furnaces vastly increased the availability of

affordable glassware; and coffee making had become a very fashionable and profitable

enterprise. While spirit lamps had been used previously to keep coffee warm in an urn, now

the heat was harnessed to drive the brewing process itself. This concept was first

employed in the early filtering percolators of the 1820’s, where heat and vapor

pressure forced water into the upper chamber of a metal drip pot. But now that concept was

expanded and made visible by the transparency of glass. Augmented by the action of the

vacuum, which initiated the second stage of the brewing process, the result was an

elegantly simple system which produced an excellent cup of coffee. |

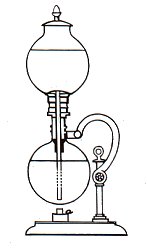

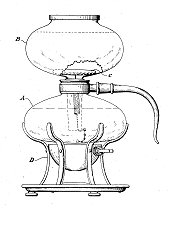

| The earliest

glass vacuum pots appear to have been in use in Germany by the 1830’s, as witnessed

by a patent filed in France by Mme. Jeanne Richard in 1838. This patent shows a design

which which referenced an existing vacuum pot by Loeff of Berlin. The popularity of the

vacuum coffee pot spread quickly from Germany to other parts of Europe, as evidenced by

patents filed by Louis François Boulanger in France (1835) and Mority Platow and James

Vardy in England (1839). It was about this time that there was an explosion of patent

filings for a variety of "improvements" to the glass vacuum pot, chief among

them being those of Madame Vassieux of Lyons. Her 1841 design consisted of a double-globe

assembly, with a spigot in the lower globe to dispense the coffee, and a decorative,

pierced-metal crown at the top. This French Balloon design is virtually

indistinguishable from the early Silex and Cona models of a half century

later. The decorative touches reflect the fact that coffee brewing had moved out of the

kitchen and into the dining room, where the new glass coffee brewers bestowed prestige

upon the hostess, and provided entertainment to her guests. |

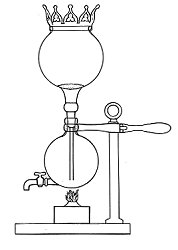

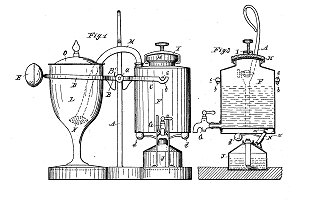

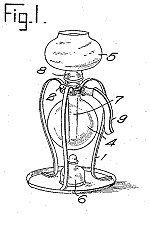

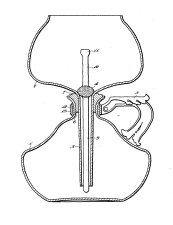

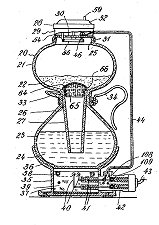

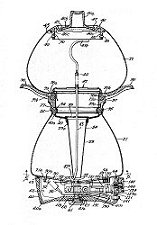

Madame Vassieux's "Glass

Balloon" design patented

in France in 1841.

|

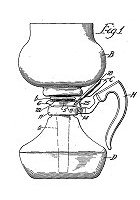

| However, these new glass coffee brewers were not without their

drawbacks. The glass of the era was nothing like the heatproof glass of the twentieth

century, and was prone to failure. Besides their obvious fragility, if the pressure was

too great, they tended to explode. And if the hostess was inattentive and the spirit lamp

was left burning after the water had left the lower globe, the glass would overheat and

crack. It was to address this latter problem that many patented improvements were filed. Various mechanisms (including one that is

rather reminiscent of the flush mechanism of a modern lavatory) were designed to

extinguish the lamp at the appropriate moment. |

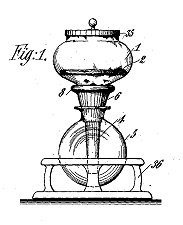

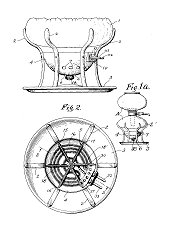

Boulanger's 1835 patent.

The first French glass

coffee maker. |

Fortant's patent design

with a self-extinguishing

flame mechanism. |

Malpeyre's 1841 patent

with a detachable handle

built into the stand. |

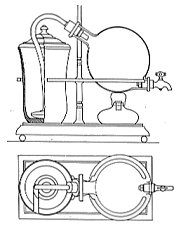

| By 1850 the double-globe glass coffee maker had generally fallen out

of favor in France, and the fashionable Parisians embraced the next incarnation of the vacuum brewer - the Balancing

Siphon. In this arrangement, the two vessels are arranged side-by-side, with a siphon

tube connecting the two. Coffee is placed in one side (usually glass), and water in the

other (usually ceramic). A spirit lamp heats the water, forcing it through the tube and

into the other vessel, where it mixes with the coffee. As the water is transferred from

one vessel to the other, a balancing system based on a counterweight or spring mechanism

is activated by the change in weight. This in turn triggers the extinguishing of the lamp.

A partial vacuum is formed, which siphons the brewed coffee through a filter and back into

the first vessel, from which is dispensed by means of a spigot. Sometimes called a Viennese

Siphon Machine or a Gabet, after Louis Gabet, whose 1844 patent included his

very successful counterweight mechanism, the Balancing Siphon was both safer than

the French Balloon, and was completely automatic. |

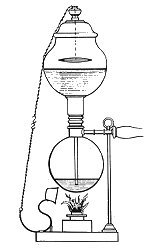

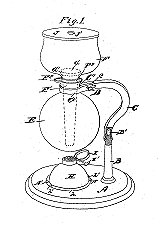

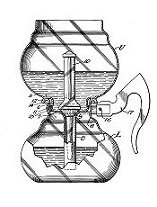

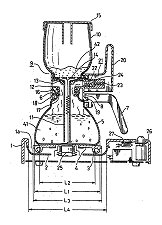

Turmel's 1853 patent for

a Balancing Siphon

coffee brewer.

|

A coffee brewing system very similar to the Balancing Siphon,

but which appears to have developed independently was the brainchild of Scottish naval

engineer and inventor, James Napier. Developed in the 1840’s, Napier’s prototype

coffee maker was composed of standard laboratory equipment, giving it a rather clinical look. The layout is nearly identical

to that of the Balancing Siphon, except that there is no balancing mechanism to

extinguish the lamp, and the brewing process was subtly different. Ground coffee and

boiling water were combined in the jar, and only a small amount of water was placed in the

globe. The water in the globe was heated by a spirit heater creating a small amount of

steam which was forced through the siphon tube to agitate the coffee and water mixture in

the jar. When the flame was extinguished, a vacuum formed which siphoned the brewed coffee

though a filter and back into the globe, from which it was served. The Napierian

brewer was much preferred in England, and stunningly beautiful silver-plated versions

continued to be made into the early part of the twentieth century. |

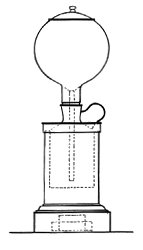

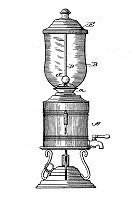

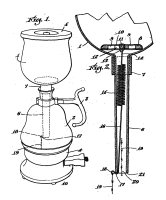

Roberton's 1890 patent

for an improved Napierian

brewer with a spigot added

to the glass globe.

|

| In 1894, the House Furnishing Review reported the arrival in America of a new patented

English coffee machine, composed of a "glass globe or boiler which hangs by means of

trunnions from an ornamental stand, the base of which is a spirit lamp. A funnel-shaped

vessel, terminating in a long glass tube, the junction being surrounded with a cork

fitting the mouth of the boiler, forms the remaining portion of the appliance."

This "new" machine was obviously a revival of Mme Vassieux’s 1841 French

Balloon. |

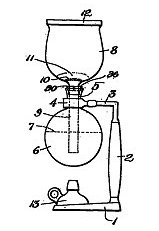

When the glass vacuum pot was re-introduced in the

early part of the twentieth century, it was accepted as a new and unique American

invention, despite its long history in Europe. Interestingly, most modern writers who do

acknowledge the vacuum coffee brewer’s European antecedents usually associated it

with James Napier’s side-by-side siphon brewer rather than with its true forebears,

the French designs of Vassieux, Fortant, and the like. But the vacuum brewer was already

known in America as early as 1859. A number of early patents describe metal pots which

employed the vacuum principle to brew coffee, including that of William Edson of Boston,

Massachusetts, who, in 1866, patented his inexpensive and easily-constructed

"Improved Coffee-Pot":

The spirit of my invention

consists in making a coffee-pot with a single diaphragm being provided with pipe P, the

whole being arranged, in combination with the closed pouring-spout B, that when the water

in the lower chamber boils it shall be forced, by its own steam, into the upper chamber S,

and that when the whole begins to cool a vacuum shall be formed in the lower chamber, and

forcibly draw back through the pipe P the liquid coffee from the upper chamber, S, leaving

the grounds upon the strainer F.

I am aware that this same object has been completely accomplished by a French invention,

(see Veyron’s Brevet d’Invention,) called the "vacuum coffee-pot;" but

the arrangement is complicated and expensive…I do not think there has heretofore been

invented a coffee-pot in which the complete operation is secured by means so simple as

mine.

|

Early Silex Vacuum Brewer,

nearly identical to the

French Balloons of the 1840's.

Edson's 1866

"Improved Coffee-Pot"

|

In 1868, Julius Petsch of Hanover, Prussia, and

Stephen Buynitzky of St. Petersburg, Russia, jointly filed a U.S. patent for an ingenious

vacuum brewer consisting of an integrated pot with internal upper and lower chambers,

suspended by trunnions from a stand over a spirit heater. Due to the asymmetrical shapes

of the two chambers, when the water rises to the upper chamber, the pot becomes unbalanced

and tips to the side. This process extinguishes the heater, and when the vacuum pulls the

brewed coffee back into the lower chamber, the pot swings back to vertical, simultaneously

tripping a small hammer which then strikes a bell to indicate that the coffee is ready.

In 1866 and again in 1887,

patents were filed for side-by-side Balancing Siphon pots which were virtually

identical to Gabet’s 1844 design, including his patented counterweight mechanism.

|

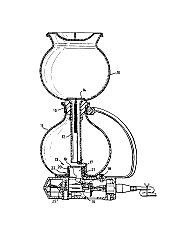

Petsch and Buynitzky's 1868

Coffee Making Apparatus

|

Freiderich Liesche's 1866

Balancing Siphon Apparatus |

Edgar Perdelwitz's 1887

Machine for Infusing Coffee |

| The first stacked vacuum coffee pot design patented

in America of which a significant component was composed of glass, was James Van

Marter’s 1898 design consisting of a lower metal chamber surmounted by a cylindrical

glass upper chamber. An airtight seal was formed between the two chambers by wrapping the

roughened surfaces with linen tape. By brewing the coffee in the closed upper chamber, Van

Marter assures us that his apparatus will achieve "the thorough extraction of all the

desirable elements [of the coffee-berry] without any loss of the volatile aromatic

portions thereof." Again, this design was not totally new, and indeed appears

to be a copy of the Repalier-style vacuum pots popular in Europe in the 1850's. |

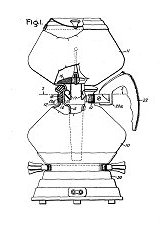

Van Marter's 1898

Metal & Glass Coffee Apparatus

|

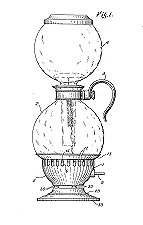

A recognizable double-glass vacuum pot does not

appear in the patent records until 1914 - a "Coffee Percolator" designed by

Albert Cohn of London. This design is clearly the direct descendent of Mme Vassieux’s

French Balloon. That year also saw the design of an early Silex vacuum brewer

designed by Gerhard Behrend of New York. A flurry of similar design patents were

filed in the subsequent few years, all consisting of upper and lower glass vessels fitted

together with a flexible stopper, some type of filter assembly, and a base to support the

brewer over a spirit lamp. Because the glass vessels of this era were hand-blown,

they each varied somewhat in size and shape. As a result, many early patents pertain

to the design of handles, stands, and rubber seals that could adapt to these

variations. A number of double-glass balloon vacuum pots appeared in the patents

with imaginatively designed support stands.

|

Albert Cohn's 1914

Design Patent for a

"Coffee Percolator"

|

Richard Darling's 1915

"Bracket for Glass Percolators"

|

Jacob Bleichrode's 1918

"Coffee Percolator with

Flexible Coupling"

|

Henry Task's 1916

"Coffee Percolator" with

detachable handle

|

| In 1915, a vacuum coffee maker was made from Pyrex,

the Corning Glass Work’s newly introduced ovenproof glass, and was marketed under the

name "Silex." The name reportedly derives from the phrase, "Sanitary

and Interesting method of making Luscious

coffee. It is Easy to operate on account of its being X-ray

transparent." The rights to the design had been acquired in 1909 by two

sisters, Mrs. Ann Bridges and Mrs. Sutton, of Salem, Massachusetts who had it manufactured

by the Frank E. Wolcott Manufacturing Company. With the availability of heatproof Pyrex

glass, the Silex brewers did not suffer the same drawbacks as their French predecessors,

and a new era of vacuum brewing was launched. By a fortuitous turn of events, a large

number of these Silex brewers were sold to hotels and sandwich shops, providing

large-scale exposure for the product. As a result, today the name Silex is almost

synonymous with any glass vacuum pot. |

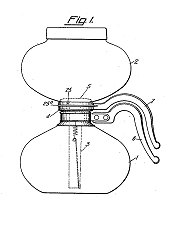

A key patent in the development of the popular Silex

line would appear to that of George Loggie of Lexington, Massachusetts. His 1917 design is

identical to the earliest Silex models, and was assigned to one Hazel M. Bridges, who

later filed the first patent on behalf of the Silex Company of Hartford, Connecticut. Mrs.

Bridges’ patent was filed in 1926 and described a "novel and improved drainer

for use in connection with the well known ‘Silex’ type of coffee

percolators," which employed a spring tensioning clip to secure the filter in place.

Her patent drawings show a freestanding vacuum pot sitting atop an electric stove.

Throughout the 1930’s, Frank Wolcott and others registered a series of patents for

improved vacuum brewers which illustrates the progression of vacuum pot designs marketed

by the Silex Company. At the 1939 New York World’s Fair, the Silex Company’s

exhibit was dominated by a seven-foot replica of a Silex glass coffee maker in operation.

|

Hazel Bridge's 1926 patent

drawing for an improved "drainer"

for the Silex brewer

|

1934 Silex

Coffee Maker

(Anne M. Boever)

|

1936 Silex

Coffee Maker

(Frank E. Wolcott)

|

1938 Silex

Coffee Maker

(Frank E. Wolcott)

|

| The main competitor to the Silex coffee makers was

Harvey Cory's Glass Coffee Brewer Corporation of Chicago, Illinois. The first

patent filed by Harvey Cory for a vacuum coffee brewer was in 1933, and was quickly

followed by a series of new designs, many of which focused on peripheral design elements

of the brewers - handles, covers, filters, and so forth. His 1934 patent illustrates

both the "Fast-Flo" filter which shipped with many early Cory brewers, as well

as an alternate design which showed up later on vacuum pots sold by General Electric. It

is interesting to note that what is arguably the most significant innovation ascribed to

Cory, namely the glass filter rod, was not invented by Harvey Cory himself, but by Raymond

Kell of the MacBeth Evans Glass Company in 1932. The familiar Cory design was patented in

1939, while the similar Silex "Lox-In" glass filter was not submitted for patent

until 1946. |

1935 Cory vacuum brewer

with flip-up decanter cover

|

1936 Cory patent for

two filter designs

|

1932 MacBeth Evans patent

drawing for a glass filter rod

|

1946 Silex patent drawing

for "Lox-In" filter

|

The major innovations of the 1930’s were in the

electrification and automation of the vacuum brewing process. A number of electric stove

designs were patented by the Silex Company, including both commercial and domestic models,

one of which included a special stabilizing mechanism designed to keep the pots steady on

the stove aboard moving vehicles such as ships and trains. Those wishing to automate the

vacuum brewing process again struggled with the traditional problem of how to determine

when to reduce the heat to initiate the vacuum phase of the process. A number of solutions

were proposed, including designs which employed thermal detectors (Chester Hall, 1936;

Hermann Lemp, 1937) and others designed to sense the vibration of the pot caused by the

agitating action of the rising steam. Many of these were "add-on" devices, but

in 1936, Simon W. Farber of Brooklyn, New York, submitted a patent design for what would

become his fully automatic, electric "Coffee Robot."

|

1934 Silex patent drawing

for an electric stove for

vacuum coffee brewer

|

1936 patent drawing for

the Farberware electric

"Coffee Robot"

|

1937 Silex design

for an electric stove for

trains and ships

|

1937 Lemp design

for a thermal controller

for vacuum brewers

|

The 1940’s saw a number of innovations in the

design of vacuum brewers. In 1942, Harvey Cory submitted a patent for his

"rubberless" vacuum pot. This design dispenses with the customary rubber gasket

used to form an airtight seal between the upper and lower vessels, and substitutes a seal

formed by two mechanically ground glass surfaces. The seal is rendered fluid tight by the

combined weight of the upper bowl, filter and ground coffee. The key to this design is to

ensure that the pressure required to raise the water up the funnel tube does not dislodge

the upper vessel before the weight of the water above compensates for the increasing

pressure below. Another innovative design introduced around this time was the sleek and

futuristic-looking General Electric vacuum brewer. The GE "Automatic" model

incorporated a unique, magnetically-activated device to control the brewing process.

|

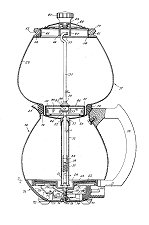

1941 patent drawing for

the Cory "Rubberless"

vacuum brewer

|

1935 design for the

General Electric

vacuum brewer

|

General Electric's 1939

design incorporated a thermal

control mechanism attached to

the upper chamber |

General Electric's 1942

design for a magnetically

operated control mechanism

|

The decade of the 1940’s also saw the emergence

of Sunbeam’s highly successful "Coffeemaster" line - a series of polished

chrome electric vacuum brewers which incorporated an automatic system to control all

aspects of the brewing process:

A further object is to

provide what may be termed an automatic coffee maker, which will function automatically to

perform the coffee making operations and to keep the coffee at a desired temperature for

serving. In this connection my invention aims to control the timing of the coffee making

functions, regardless of the number of cups of coffee being made, to the end that

uniformly delicious coffee will be produced with out need of the housewife or operator

keeping watch over the device to perform some manual operation in the nature of timing, or

adjusting, or preventing recurrence of the coffee making process.

|

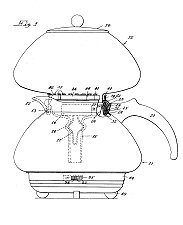

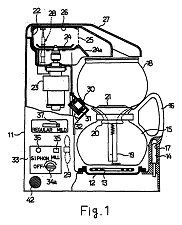

1940 patent drawing for

a Sunbeam electric

vacuum brewer

|

1943 patent drawing for

the Sunbeam "Coffeemaster""

automatic vacuum brewer

|

1938 patent drawing for

an early Sunbeam

"Coffeemaster" model

|

By the middle of the 1950’s, the vacuum pot had

begun to fall out of favor and the number of patents filed fell dramatically after about

1951, with the final patent for a vacuum coffee maker in this era being filed ten years

later by Chester Wickenburg, et. al. of the Sunbeam Corporation. The vacuum pot was

gradually supplanted first by the pumping percolator, and later by a descendant of the old

French Drip pot: Mr. Coffee and his kin.

As the twenty-first century

dawns, the popularity of the vacuum pot is experiencing something of a renaissance, fueled

by those individuals who appreciate fine coffee and by those who are attracted to the

nostalgia of its Art Deco appeal. A handful of companies still manufacture and sell

vacuum brewers, most notably Asian firms such as Hario, Yama, and Tayli. In 1989,

Toshiba patented a microchip-controlled vacuum brewer in which the brewing of the coffee

(including the grinding of the coffee beans) is performed automatically based on

electronic input of the number of cups and strength desired.

|

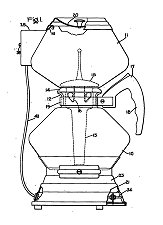

1961 patent drawing for

the Sunbeam Electric

"Coffeemaster"

Model C50

|

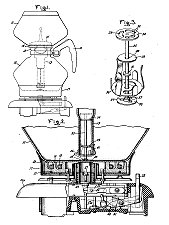

Sharp's 1988 patent

drawing for an electric

vacuum brewer

|

Toshiba's 1989 patent

drawing for a microchip

controlled vacuum brewer

with built-in coffee mill

|

Chiaphua Industries' 1999

design for an electric

vacuum brewer

|

| If history again repeats its 100-year cycle, the next

couple of decades should witness the emergence of a modern incarnation of the vacuum

brewer which may again delight the coffee enthusiast and spark the enthusiasm of the

general public. |

| References |

| Edward & Joan

Bramah. Coffee Makers - 300 years of art & design.

(Quiller Press, Ltd., London. 1995) |

| Carroll Gantz. 100 Years of Design - A Chronology 1895-1995.

(Industrial Designers Society of America. 1996) |

| Corby Kummer. The Joy of Coffee. (Chapters Publishing, Ltd.,

Shelburne, VT. 1995) |

| Mark Williams. Expo Archive: 1939-40 New York Worlds Fair. (World

Wide Web) |

| United

States Patent & Trademark Office. (World Wide Web) |

|

| Note: All trade

names and patent drawings referenced in this article are the property of their respective

owners. |

|